The blade was probably an inch from his throat, maybe closer. He was too drunk to remember all the details. The only thing Joey McCreedy remembers is waking up strapped to a bed in a psychiatric ward the following morning, just a few hours after threatening to commit suicide in his mother’s bedroom while his 7-year-old brother looked on.

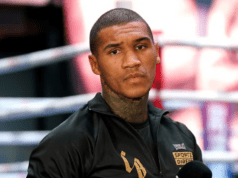

Once considered the pride of Lowell, Mass. – the young, handsome football star, the darling of the family, the next Micky Ward in and out of the boxing ring – McCreedy had finally hit rock bottom.

Years of masking his on-again, off-again depression with excessive partying and drinking drove him to the edge. The pressure of following in the footsteps of a regional icon, the feeling of failure after losing the biggest fight of his career in Vegas, an entire city turning its back on him, all of it left McCreedy searching for a way out.

The turmoil reached its boiling point one night when McCreedy, already intoxicated following an argument with his girlfriend, who had grown tired of his drinking, went back to the liquor store, bought more alcohol and began mixing it with prescription sleeping pills.

“For some reason, I went downstairs, grabbed a knife, walked into my mom’s room and said, ‘Mom, I love you. Goodbye. I can’t take this anymore.’ I was numb.

“I gave up on myself.”

The 30-year-old McCreedy (15-8-2, 6 KOs) begins his long-awaited comeback Friday, Dec. 18th, 2015 on the undercard of CES Boxing’s “Holiday Bash” at Twin River Casino in a six-round bout against Texas’ Emmanuel Sanchez (6-4, 1 KO), his first fight in more than a year.

He’s much leaner than the last time he fought, no longer tipping the scales at 175 pounds, instead fighting closer to the middleweight limit of 160. He was in such good shape throughout this recent training camp he actually had to put on a few pounds to meet Sanchez in the middle at 165.

This isn’t the same McCreedy who, while training for his September 2014 bout against Rich Gingras, used to come home every night from the gym and polish off a couple of bottles of alcohol in his room. McCreedy knows this is his last chance to not only get back to the top, back to where he was that night in Vegas when he fought for a title against Sean Monaghan at the MGM Grand – the pinnacle for most promising fighters – but also to silence those who doubt he has much left in the tank.

McCreedy has always cared what other people think, perhaps to a fault, so when he returned to Lowell following the knockout loss to Monaghan, it hurt him to see so many people turn away, people who had once extended a hand or lent their support. Such is the case in boxing. Life is great at the top when friends come out of the woodwork, but the fall from grace is painful and lonely.

“I lost friends. I lost best friends,” McCreedy said. “A lot of people just gave up on me, just like they did with Micky when he was young.”

That emptiness only drove McCreedy to drink more. His depression worsened following the loss to Gingras, a fight he only agreed to so he could cash his paycheck and buy more liquor.

“I was thinking about Vegas, I was thinking about Lowell, I was thinking about my girlfriend, I was thinking about how I had a chance at the biggest shot in the world and I fucked it up,” he said. “I kept drinking, drinking and drinking.”

McCreedy firmly believes hitting rock bottom, the night he held the knife to his throat, just seconds from taking his own life, was a necessary chapter in the story of his recovery.

“God knew I was stubborn,” he said. “God knew I wasn’t going to get help so he said, ‘OK, we’re going to do it the hard way.'”

Had his mother not intervened, knocking the knife from his hand and tackling her on to the ground – “I don’t know she did it. They say mothers have that super mom strength,” he said – McCreedy would still be on the same path toward self-destruction, perhaps with a much grizzlier ending.

Under heavy medication for the next two weeks, bound in a straight jacket and locked in a cramped, one-room cell with only a hint of sunlight peering in through a tiny window, McCreedy faced his worst fears.

“I was literally on the same floor with people screaming and yelling,” he said. “It was like some shit you see in a movie.”

IT TOOK TIME, but McCreedy eventually opened up. With the help of a psychiatrist, he dug deep to the root of his depression, the burden of trying to emerge from Ward’s shadow, the pressure of losing on boxing’s biggest stage, dealing with bipolar disorder and mood swings. He understood what he had put his family through. He recalled his high school years as a star football player, never having to worry about grades, and the inevitable realization that the sport was merely a pastime, not a career.

McCreedy left the hospital with a second chance at life. He blocked out the negative influences, left behind his connection to Ward and Dicky Eklund, both of whom were larger-than-life figures in Lowell, and began training at the nearby West End Gym.

When he says this is the new Joey McCreedy, he’s sincere. No more drinking, no more partying. He’s got a new job, a new car and an incredible story to share with others in hopes that it’ll one day steer someone in danger toward the right path.

“Everyone deals with depression in a whole different way,” he said. “I figured, let me get me story out there. Maybe I can save a life.

“I’m a different person. I think different. I can’t explain it. It’s something you have to go through yourself, but if I can do this, anybody else can.”

The result in the ring Friday is almost inconsequential at this point. McCreedy has already won the most important battle.