Boxing History of the 1880s & Champion John L Sullivan

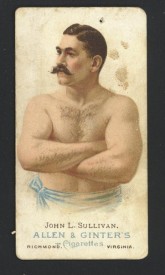

Ask a boxing fan the name of the first heavyweight champ, and it’s dollars to donuts that the answer will be John L. Sullivan. He’s certainly among the handful of the readily recognizable. Most people, whether fans of the Sweet Science or not, will at least have a vague awareness of his name, just as they’ll know Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis, Rocky Marciano, and Muhammad Ali. But as preeminent boxing historian and writer A.J. Liebling has astutely observed, before there was the great John L., there was simply Sullivan — hit by “Paddy Ryan, with the bare knuckles, and Ryan by Joe Goss”, tracing the succession of boxing history from one fighter to the next.

The State of Boxing

Goss and Ryan fought under the Revised London Prize Ring Rules, which had been introduced and established in 1853, and were to remain in place in America until superseded in 1889 by the Marquess of Queensberry Rules. The London Rules were nothing if not open minded. A bout, for example, could proceed for any number of rounds. And a round ended only when one of the men was knocked down (or even wrestled to the ground). He would be given a 30-second rest, with an additional eight seconds to “come to scratch” — a line drawn in the center of the ring where he must once again stand toe-to-toe with his opponent. Should he be unwilling or unable to do so, the bout would end with the other man declared the winner.

Englishman Joe Goss fought only twice on American soil. He took the championship from Tom Allen in 1876, losing it to Paddy Ryan in 1880. The latter fight went 87 rounds. Ryan holds a unique record in the annals of boxing, winning the championship in his first professional bout…and losing it in his second. John L. Sullivan took the title from Ryan in 1882, the last fighter to win a championship under the revised London Rules.

Of course, it’s important to note that polite society considered boxing barbaric, and held sufficient sway over lawmakers to ensure that matches were illegal in most jurisdictions. This is why one reads about this or that bout taking place on a barge, hopefully beyond the reach of the long arm of the law. The alternative was to hold fights surreptitiously, late at night and in secluded locations. Still, if discovered, the police would break up the matches. In 1868, for example, the police arrested Joe Coburn before he could face Mike McCool. The canny “Deckhand Champion of America” then entered the ring in his boxing togs, and was declared champion.

But declared by whom? There were no boxing associations at the time, and therefore no officially recognized champions. The “title” Sullivan took from Ryan was that of Heavyweight Champion of America, an honorific bestowed by the fans. While Sullivan’s championship has since received history’s imprimatur, there were not official sanctioning bodies for several decades to come.

The Rise of John L. Sullivan

That said, Sullivan was indeed America’s bare-knuckle champ, and the winner of the last bare-knuckle championship fight. Still, he was far from just a “bare knuckle” fighter. In fact, he only fought bare knuckle on several occasions over the course of his career. With time and victories, he was recognized as the first Heavyweight Champion of the World.

That said, Sullivan was indeed America’s bare-knuckle champ, and the winner of the last bare-knuckle championship fight. Still, he was far from just a “bare knuckle” fighter. In fact, he only fought bare knuckle on several occasions over the course of his career. With time and victories, he was recognized as the first Heavyweight Champion of the World.

The “Boston Strong Boy” made a name for himself by defeating John Flood, the “Bull’s Head Terror”, in 1881. Sullivan knocked Flood down for eight consecutive rounds over the course of about 15 minutes. The beating clearly served to remind the “Terror” of an old proverb — something about discretion and valor — and he wisely quit.

Following his decisive win over Flood, Sullivan scored victory after victory. Among his victims were Fred Crossley, knocked out in the first round, and Captain James Dalton, kayoed in four. But the fight that made him the “Champion of Champions” took place on February 7, 1882: Sullivan vs. Ryan.

Ryan proved no match for the more powerful Sullivan. Given that the rules of the day allowed for what amounted to wrestling, Sullivan was able to use his superior brute strength to overwhelm his opponent. Ryan was battered and exhausted by the ninth, at which point Sullivan finished him.

The one-sided bout is important not only because it established Sullivan as champ, but also because of the national and international interest it garnered. In addition to journalists, notable American and foreign writers were commissioned to cover the bout, including Henry Ward Beecher and Oscar Wilde.

Both at home and overseas, the new heavyweight champ took on all comers (though he avoided black challengers), including Herbert Slade, a Maori. In his 1887 bout with Patsy Cardiff, Sullivan broke his left arm in the first round, but nevertheless went on to fight a six-round draw. He toured the U.S., offering $1,000 (about $25,000 today) to any man who could stand against him over four rounds.

One of Sullivan’s most notable fights, if only because of its international flavor, took place at Baron Rothschild’s estate in Chantilly, France. The best the champ could do against the Englishman Charlie Mitchell was a 39-round draw. Boxing was illegal in France at the time, and both men found themselves short-term guests of the local gendarmerie.

In what proved to be the last bare-knuckle championship bout, the last fought under the Revised London Prize Ring Rules, Sullivan faced Jake Kilrain on July 8, 1889. Ironic that the illegal match, which took place in Richburg, Mississippi, was refereed by John Fitzpatrick, future New Orleans mayor, while Bat Masterson, former Dodge City sheriff, served as Kilrain’s timekeeper. And the illegality of the bout didn’t stop the presence of Captain Tom Jamieson and 20 of his Winchester-toting Mississippi Rangers.

Sullivan redeemed himself in this fight, following his unsatisfactory bout with Mitchell. It lasted more than two hours in blistering heat, Sullivan winning when Kilrain’s corner threw in the sponge in the 75th round.

With the introduction of the Marquess of Queensberry Rules, following the Sullivan-Kilrain match, the era of the bare-knuckle brawler ended and that of the boxer began — an era over which a man by the name of James J. Corbett would reign.

More Boxing History

1820-1860: Last British Stars ←1880s -> 1890s: Corbett & Fitzsimmons