Bill Richmond and Tom Molineaux: The Black Challengers and the Beginning of the End for Britain’s Rule of Boxing

By the early 1800s, following the thrilling trilogy between Daniel Mendoza and Richard Humphries, the sport of pugilism was thriving. Tom Cribb and Jem Belcher were Britain’s next best, and enthralled the masses. However, this era was not only significant for the champions who reigned. Pugilism was the first sport to allow members of opposing races, religions and nationalities to compete against each other. Nobody embraced this more than Bill Richmond and Tom Molineaux. Their names may not be recognized today but their legacies are; the importance of these two men in the history and progression of black athletes, and the transformation of pugilism into an international sport, cannot be understated.

Born a slave in Staten Island in 1765, Richmond was taken to England aged thirteen, by Lord Percy, a British general who served in the War of Independence. Lord Percy soon realized the potential of the bright, energetic teen. He removed Richmond from work and sent him to be educated.

Richmond’s new privileged upbringing brought troubles in adulthood. His skin color, fancy clothes and intelligence enraged many people. Often involved in bar room brawls, it wasn’t long before he had gained a violent reputation, and was convinced pugilism was his destiny.

Richmond became known in London sporting circles and in 1804 fought his first professional fight against fifty year old veteran, George Maddox. This turned out to be a mistake as the inexperienced Richmond was battered inside three rounds.

Showing courage and determination, Richmond returned to the ring in 1805, taking on, ‘Fighting Youssop’, the self-proclaimed Jewish champion. ‘Fighting Youssop’ was a huge brute of a man and in round one almost punched Richmond out of the ring. However, the American, by far the quicker of the two, soon began beating Youssop to the punch. Following six rounds ‘Fighting Youssop’ could take no more and quit on his stool.

Richmond’s reputation was made but his next opponent, a rising star named Tom Cribb, was a much superior fighter. Cribb toyed with Richmond and made him look a fool. Afterwards, Richmond realized he was not good enough to become a champion, and reluctantly retired. Though he did make a number of sporadic comebacks, it was at this time he found his true calling – as a trainer.

In 1809, Tom Molineaux, an African American and a former slave from Virginia, arrived in England. The twenty five year old had a hard youth, forced into fighting fellow slaves. He had an unruly style, which was rough and raw – certainly not the Sweet Science. On arriving in London he needed a trainer and naturally gravitated to his compatriot, Richmond.

Victories over Jack Burrowes and Tom ‘Tough’ Blake, demonstrated the American’s power and effective aggression. It wasn’t long before the new champion of England and the man who had beaten Richmond four years earlier, Tom Cribb, was on his radar.

Backed by an array of the British gentry, Cribb was considered a gentleman of the sport and Britain’s finest fighter; he couldn’t ignore a challenge by a black man.

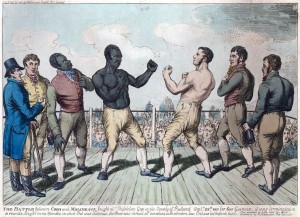

A title fight was arranged for December, 18, 1810, on an erected stage near Sussex. In a clash of styles, Cribb’s, upright hitting and moving would be tested against Molineaux’s wild haymakers, jabbing and excessive holding.

The winter air was bitterly cold and rain pelted down. Molineaux, unaccustomed to fighting in such conditions, looked worried as he, and trainer Richmond, shivered their way to the stage, subjected to tirades of racist abuse.

Cribb, believing he was fighting a novice, barely trained for the fight and went toe to toe with Molineaux, who soon took control. Twice the volatile crowd burst into the ring as the American seemed poised to knock Cribb out. The second such instance resulted in Molineaux’s finger being broken.

The controversies continued as the battle rumbled on. In round twenty-seven, Cribb was already beaten to a pulp when a booming right bounced off his skull sending the champion to the hard, wooden floor. The umpires however permitted him time to recover. Semiconscious, swaying on unsteady legs and muttering nonsensically, he stumbled towards Molineaux. The American delivered just one right hand and Cribb was knocked out.

The crowd fell silent. All that could be heard was the shrieking celebrations of Richmond and Molineaux. In a frenzy of desperation Cribb’s trainer, Joe Ward, stormed onto the stage throwing punches at Richmond, falsely claiming Molineaux had weights in his hands. By the time the umpires regained order fifteen minutes had elapsed and Cribb, having gulped down near half a bottle of brandy, was up and ready to fight. This time Cribb chose not to trade shots but to stick to his usual style, moving around and fighting on his toes.

By round forty, Molineaux, now drenched in rain, sweat and blood, close to exhaustion and disheartened by the crowd and umpires, uttered the immortal words “I can fight no longer.”

Although furious at the injustice, Richmond knew British society would not take kindly to a black man crying foul, especially against a hero like Cribb. However, after a few carefully worded challenges in the press, Richmond soon got the public interested in a re-match.

In 1811, the pair met again, this time near Leicester in front of a staggering 20,000 supporters. While in the first fight Cribb had been underprepared, this time it was Molineaux who was out of shape. As a famous black sportsman he A black fighter who had had become something of a novelty in British popular culture and toured the country attracting thousands of paying fans to his exhibitions. But with a gargantuan appetite for women, food and drink, he soon became uncontrollable. On the morning of the rematch, Richmond could only look on in horror as his charge ate a boiled fowl and a full apple pie, and washed it down with a tankard of ale for breakfast.

This time Cribb started the better. He darted around smashing home combinations, softening up his opponent. After less than twenty minutes, Molineaux, jaw already broken and both eyes swollen, was knocked out.

He would never again fight for the title. If not for blatant cheating at Sussex in 1810, Molineaux would have been the first black boxing champion. Instead, unable to deal with fame and fortune, he died penniless in Ireland in 1818, aged just thirty four. Despite a disappointing end, he achieved a huge amount and demonstrated that black challengers could compete at the highest level.

Richmond became a respected statesman of the sport, and by the 1820s was considered Britain’s best trainer. He was entrusted to many white champions, including his old adversary Tom Cribb, but it was his work with black boxers which became most significant. Under the guidance of Richmond an array of black fighters would forge successful careers. The other major ethnicities represented in boxing at this time were the Irish and Jewish fighters, and they reach relied on their own communities for funds. With no such organized black community, it often fell on Richmond to work tirelessly in gaining backing for these fighters.

Richmond was not the first black man to fight in Britain but he was the first to gain nationwide respect and fame. He proved that black people could compete, organize and teach the sport in a professional manner. Although full acceptance was a long way off, the first steps had been taken.

Richmond and Molineaux also opened doors to other fighters from around the world, eager to prove their worth against the British. With more and more challengers emerging, Britain began losing its stranglehold, and pugilism, once considered a solely British pastime, was fast becoming the world’s first international sport.

More Boxing History:

Humphries & Mendoza – Boxing in the Late 1700s ← Early 1800s →Mid 1800s: The Last British Stars