Humphries, Mendoza and the revival of pugilism

Throughout the 1750s, 60s and 70s, following the demise of Jack Broughton when the upper class patrons all but abandoned the sport, pugilism was driven into the back streets of Britain and became even more illegal, immoral and deadly. Fans who braved such conditions were just as likely to suffer injury as the fighters themselves, and there seemed to be no hope of pugilism ever gaining respectability.

Despite the laws which suppressed pugilism, in the cruel age of the eighteenth century where pain and hardship was a part of life, this, the roughest of all sports, was still supported by the working classes. Although damaged, pugilism had not died, and similarly to today, was just in desperate need of popular and enigmatic fighters to reignite its place in popular culture.

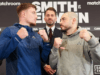

Richard Humphries and Daniel Mendoza were just the men and their heated and much publicized rivalry catapulted the sport back into the public eye.

Humphries had the looks and manners of a gentleman. He was a brave, upright fighter, who soon became the embodiment of English strength and defiance. The British fans loved him, as did the nobility, who Humphries helped return to the sport, and by 1786 he had cemented his fame by beating, Sam ‘The Bath Butcher’ Martin, at Newmarket racecourse.

Boxing Becomes the Sweet Science

Daniel Mendoza was the complete opposite and a perfect adversary for Humphries. He was a dark, fiery and flamboyant Jew from the poverty stricken slums of Whitechapel, East London. Although rough and ready outside the ring, when fighting he was smart and controlled. Mendoza is credited with being the first scientific boxer who relied on footwork and defense more than power and strength. Always quick to use his fists when hearing anti-Semitic abuse in the streets, he was determined to quell popular stereotypes and prove that Jews could be strong and brave. He too made his name with a victory over ‘The Bath Butcher’ after which the public demanded a showdown with Humphries.

The press heavily favored Humphries. They ridiculed Mendoza’s defensive style calling him a ‘cunning Jew’. In fact most newspapers simply referred to him as ‘The Jew’. At this time, Jewish immigrants, fleeing persecution in Europe, were arriving in England, flooding the already overcrowded slums created by Britain’s expanding industrial revolution. The Mendoza – Humphries fights were promoted as ‘The Englishman versus The Jew’ and exploited racial tensions growing in Britain’s new inner cities. The pair traded words in the press and the public became fascinated with the bout. The fight was arranged for 1788, with the winner expected to take on Tom Johnson for the heavyweight championship of England.

This first encounter was nothing short of a debacle. Both men were slipping and sliding on the rain soaked stage before Humphries prevailed, although many believed Mendoza wasn’t given a fair deal by the officials and the crowd. This was, however, followed one year later by a sensational win for Mendoza. He outworked and out maneuvered Humphries, patiently waiting for openings before striking. After almost one hour and sixty-five vicious rounds, Humphries, who was bleeding profusely from both eyes, was finished and Mendoza emerged victorious. The sporting public were now desperate for a final decider. In a similar contest, Mendoza dominated, jabbing and moving throughout, although it took him a grueling seventy-two rounds to win.

Despite the anti-Semitism of the time, Mendoza, in the toughest of all sports, had proved himself a worthy champion. He was propelled into the limelight even becoming the first Jewish person to be invited to Buckingham Palace. In the ring, he enhanced his claim as the champion of England with two victories over Bill Ward before controversially losing his title in 1795. His opponent was the much loved ‘Gentleman’ John Jackson.

In front of a huge crowd, including a host of the gentry who favored Johnson, the pair were involved in one of the most infamous fights of the era. In round four, Jackson held Mendoza by his long hair and smashed a number of strong shots to the face of the stricken champion, though the umpires chose not to punish the offence. By round nine Mendoza was a battered, bruised and bloody mess and a new champion was crowned. Despite this less than glorious incident, Jackson became a respected champion who ironically went on to umpire bouts. He even took up teaching the sport to wealthy young men and his client list included the famous poet Lord Byron.

Despite being technically illegal, pugilism, with popular stars and action packed fights, was enthralling both the masses and wealthy elite. Daniel Mendoza, ‘Gentleman’ John Jackson, Richard Humphries, Tom Johnson and many more excited the fans during this period. Although still in a rather desperate state, pugilism had risen from the darkness of the past few decades. Yet the Mendoza – Humphries trilogy set a dangerous precedent in which the press and promoters eagerly whipped up racial hatred for commercial gain – a trait which continued well into the twentieth century and many would argue is still with us today.

More Boxing History:

Mid 1700s – Broughton’s Rules ← Late 1700s → Early 1800s Richmond, Molineaux & Cribbs