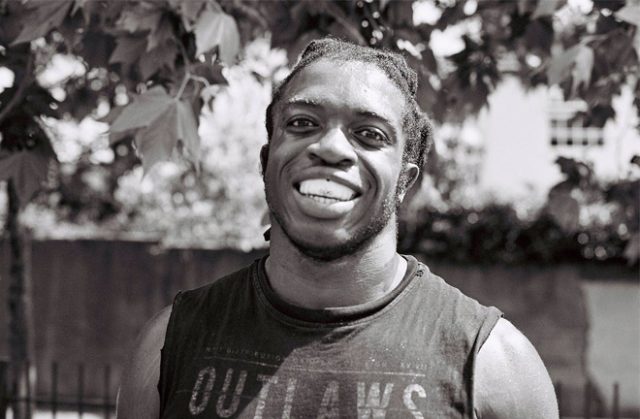

Franklin Ignatius is, to all intents and purposes, an archetypal heavyweight boxer. A big man with an imposing physique coupled with a booming, authoritative voice: like bangers and mash it is a tried and tested combination that works every time.

The more I spoke to the 25-year-old the more I was taken aback by his remarkable life experiences. Impressive was his ability to remain the gentlest of giants despite past experiences leaving him with a heavy heart.

We began our conversation, amid the backdrop of Black Lives Matter protests in London, by discussing his childhood in Austria.

“I grew up in Linz,” Ignatius explained, “where my parents had emigrated to from Nigeria and I was the only black kid attending my school. It was tough, there was a lot of ignorance that you had to deal with at the time.

“As a result your parents are having to step in and defend you and you’re being put in situations you shouldn’t be in as a kid.

“It toughened me, I guess, so by the time I ended up, essentially, in Barking there were a lot of different ethnicities and cultures around me and that was eye-opening.”

Ignatius moved to the Barking area aged 11 at a time where the British National Party, spearheaded by Richard Barnbrook were the opposition party in the local council. Indeed, national leader, Nick Griffin famously said, “don’t come to Barking if you want diversity.”

Ignatius’ experiences of the area couldn’t have been more different. From his early years in Linz his new home represented a vibrancy of culture. Racism remained hard to avoid, however.

“Frustration has always been a close companion for me. People would look at me funny because I had a different accent to them. Coming to London I sounded weird because my English was a mix of a German and a Nigerian accent.

“I didn’t have any of the cool clothes, I didn’t have the latest fashion, I was 11 years old and it was a recipe for people to take the piss.”

Looking back on that time he admitted that his frustrations and anger were released when he hit the pads for the first time – not, in earnest, until he was 18. I asked him if he wished he’d turned to the gym earlier but he was honest in explaining why that wasn’t the case:

“My first proper experience in boxing came when I was at [Liverpool] University and I just looked for the nearest gym. It lit a fire within me, to be honest, but when you start boxing at that older age you’re more mentally prepared for what is required of you.

“As a kid, and a teenager, I didn’t have any discipline and I was a bit of an unruly kid but I wouldn’t have been able to be as dedicated and focussed as I was when I started at Uni.”

The friendly city of Liverpool was a place for Ignatius to escape: a degree in, his favoured subject, English and Communications allowed the previously “unruly kid” to deep dive into his passions.

Walking into the gym was a culmination of emotions harboured over the years so perhaps it was no surprise that his ferocious power was immediately obvious.

“I’ve always had natural power and even when I was hitting the pads as a kid I was very, very heavy handed. Going to the gym was more about learning how to channel that effectively and maintaining fitness.

“The only thing I did before boxing was power-lifting and that involved short bursts of explosivity so stamina wasn’t really my thing at the beginning. I loved training, I really did, and I’ve always been keen to get in the ring and learn as much as possible.”

As an amateur he boxed out of Repton for two years and, along the way, won the Haringey BoxCup, London Elites and ABA Intermediate championships. I asked him how that had developed his confidence and, moreover, reminded him of a contentious loss to Jeamie Tshikeva at the 2015 London Elites in which Ignatius had a point deducted.

“Going to Repton was one of the best things I ever did because, once the coaches saw you in sparring and saw you were dedicated, they would give you as many opportunities as possible. They really believed in you and that is always going to be a good thing for your development.

“Fighting Jeamie was a bit surreal, he’s a good friend of mine and we’d sparred very consistently before each of my fights. When I met him at the finals it was a case of trying to take my opportunity.”

Intriguingly it was after his first spar up in Liverpool in which Ignatius set his sights on turning professional.

A nippy middleweight, as he was described, bust up the, then, 18-year-old’s nose and Ignatius said to himself “I want more of that.”

His parents weren’t immediately convinced but were soon won over to this new path their son was carving out.

“Neither of my parents took it seriously when I started because I was a big nerd. I was reading books and playing games all day.

“I had been an amateur for a number of years and my mum was very encouraging about turning professional. She said, “it’s good because you’ve been putting all this effort in so it’s good that you’ve got this goal to work towards.”

Time and time again the conversation would return to Ignatius’ mother, Marcilina, and it was her mental strength that the heavyweight continually referenced.

It was at this point that he returned to his experiences in Austria and reflected on how his mother dealt with the prejudice faced on a daily basis.

“In Austria there was a lot of setbacks but as a kid you experience racism and discrimination in a different way. It’s smaller bites. With parents, and as an adult, it’s a lot deeper.

“They’re experiencing it at a workplace so my mum was blocked in trying to get work. She was being blocked in qualifying as a nurse in Austria despite already being a qualified nurse in Nigeria. She wouldn’t get the opportunities and all these things I’d see her cry at home about.”

Last year, in heartbreaking circumstances, Marcilina passed away having suffered from a brain aneurysm.

The impact of his losing his mother was, understandably, impossible to describe but the pain was evident from the tone of his voice.

Franklin did say, however, how grateful he was for having boxing in his life when he needed it the most: a coping mechanism better than all others.

“I have a lot of thanks to give to Martin [Franklin’s coach at Peacock Gym] for that time because he kept me busy, he kept me sparring. Because he gave me those opportunities and kept me mentally active he stopped me from slipping into depression.

“She died when we were together. She’d gone to the bathroom and by the time the ambulance came they confirmed she was braindead, essentially.

“It was obviously a traumatic time but by training and staying active it really helped me deal with those emotions.”

From countless rounds with Daniel Dubois and what seemed like an eternity in waiting it was time for Ignatius’ debut in December last year. On a Thursday night, of all nights, at York Hall the excited debutant walked to the ring around 4.30pm to take on, bulky, Bosnian Hrovje Bozinovic.

The Charlie Sims managed fighter secured a fourth round knockout with body shots ultimately doing the damage. A pleasing performance, certainly from ringside, but Ignatius rather modestly scored it mid-range.

“I would give myself a 6/10 because whilst it was a really good experience, especially emotionally, I know there are areas I could work on. I suppose you’re never going to get a 10/10 debut, especially when your opponent is just tucking up but I adapted to that and we got the stoppage.

“After the fight I said to myself that there were adjustments I’m going to have to make to get more stoppages but you have to have an engaging opponent for that to really work.”

On an emotional scale, though, the night was immeasurable and we rounded off our conversation by reflecting on the immediate thoughts racing through Franklin Ignatius’ head as Bozinovic crumpled in the final round.

For all the hurt and pain that this, quite remarkable, young man has endured there is an awful lot to admire about his persistent refusal to waver from the high ground.

“He was weak to the body, let’s be honest, and that’s how I got the stoppage: immediately [I felt] vindicated, I felt as though after everything my family had been through that year that we were able to finish it with a positive.

“We got through that time as a family, we’ll get through this pandemic as a family and we’ll achieve as a family.”