In 1974 a third-generation ‘Slogger’ was born in Barrow-in-Furness. Fathered by a blacksmith who was known as “a local fight man,” Richard T Slone had boxing in his blood from day one.

Now a globally known artist, the journey to the canvas all stemmed from boxing.

It was at four years old when Slone or ‘Slogger’ as he was known, sharing the nickname with his grandfather, father and brothers, first stepped into a boxing gym.

“My grandfather was a British boxing army champion.

“My father was a blacksmith and a local fight man. We’re from up there by the Fury’s. I’m half English and of Irish descent.

“So we’re from those days of bareknuckle fighting at the Appleby fairs and esteemed gatherings.

“My heritage has always been fighting I guess. I had been attending [Appleby fair] since I was 13.

“Obviously, I was protected by guys that were 25 and 30-years-old that wouldn’t let me bite off more than I could chew.”

The Barrow boxing gym, which is still in existence, was run by Peter Skyrme and his father, ex professional, Frank Skyrme. That was where Richard fell in love with boxing.

“It got to the point after two years of training there I used to skive off school and go to the boxing gym.

“The guy that ran the gym Peter Skyrme, he was a carpenter by trade and he would use the gym in the day time to do his woodwork. I would hit the bags whilst he would cut his wood.

“I was enthralled with boxing. I would take boxing magazines to school and I would get in trouble, we were supposed to be reading school books and I’d have a boxing magazine inside them.”

Living in a rural area such as Barrow-in-Furness, it wasn’t quite the hotspot for boxing.

At the time it was when London was thriving with regular shows at the Royal Albert Hall, Wembley Arena and of course the Mecca of British Boxing, York Hall.

“So, I was working on the door of some clubs in Barrow-in-Furness making £50 per night, which was pretty good money back then, tax-free.

“I would take that money, jump on a train and go to the fights in London.

“I would travel to London as much as I could, I’d go to York Hall.

“My family were in the same business, we all worked on the doors, so I had a pretty good job.

Captivated by the beautiful brutality of this blood sport, Slone would find any and every way possible to contact boxing figureheads whom he looked up to.

This young man from England would wax lyrical with the likes of Joe Frazier and Emanuel Steward.

“I ran up huge bills pretty much, put my family under and put a lot of stress on my parents who eventually got divorced, hopefully not just because of a damn phone bill.

“At about 14 or 15 years of age, there were phone calls to America with the likes of Emanuel Steward, Pat Petronelli [Marvin Hagler’s manager], Bob Arum and Joe Frazier.

“Guys like Petronelli and Steward took such a liking to me they would let me call up until late on reverse charges. I spoke to them once a week.”

Richard, who started calling Stateside as a fan, soon turned into a source of information for the American promoters and managers.

“At one point Bob Arum asked me what I thought of a middleweight called Nigel Benn.

“At that time I was so caught up on Marvin Hagler, so I said he [Benn] wouldn’t last two rounds with Hagler.

“But, Bob ended up signing him because of the exciting style he had.”

It was Joe Frazier and Emanuel Steward who had taken to Richard the most.

In 1989, Smokin’ Joe was in London promoting his ‘Champions Forever’ book on the Terry Wogan show.

Slone headed to London, as he often would and met up with Frazier in his hotel.

After their many telephone conversations, Joe had asked the 15-year-old Richard to show off his boxing abilities.

The pair headed to the Thomas A Becket gym where Slone would proceed to workout and impress the former undisputed heavyweight world champion.

Frazier contemplated his thoughts for a moment after seeing this teenage heavyweight standing in the gym, which was located above the pub of the same name on the Old Kent Road, where Henry Cooper made himself a British Boxing icon.

After gathering his thoughts Joe turned to the Cumbrian and told him to finish school, make his own way to Philadelphia and proceeded to offer to train him.

“I was over the moon. I left London and went back to Cumbria with a whole new vision that I was going to be a fighter.

“I learned every day, I studied Joe like nobody else so I could impress him.

“May 1990 I jumped on the plane, I had never been on a plane before, I booked a really cheap flight so it went to Boston to Detroit and finally to Philadelphia.”

‘Slogger’ landed in Philly with only $40 and a pair of gloves. After flying for the first time and a trip which seemed an eternity with numerous connections, it was all made better knowing Marvis Frazier, Joe’s son was waiting at the other side for him.

“I sold my belongings in England. I had one of the first flat-screen TV’s, I sold that. I had about four VCR players, I sold all of those.

“I got the money together and paid for my flight.

“Marvis picked me up from the airport and took me to the gym, it was late at night.”

Slone continued; “I woke up all discombobulated after a long journey, I had no idea where I was.

“I went downstairs, it was the middle of the ghetto, the worst neighbourhood in Philadelphia.

“I stayed there maybe eight to ten years. In that time I became Joe’s, right-hand man.

“In sparring, I’d emulate his style I just never had that heart or willpower he had. He demanded that everybody fights in the style, it was brutal.

“I wasn’t quite as big or strong and at that point, the heavyweights were bigger. I did a lot of rounds with Bert Cooper.

“I sparred with David Bey, Tim Witherspoon, a lot of these guys who were just big dudes. Tex Cobb, Tex Cobb was a monster!”

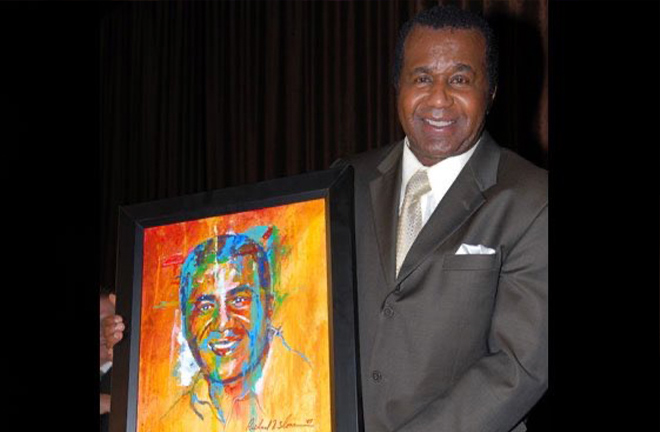

Later in life, it was the Kronk gym, in Detroit that Slone would call home.

A friendship with Emanuel Steward had blossomed from the many phone calls ‘Slogger’ made to America as a teen.

“It was in Leeds where I met Emanuel Steward for the first time.

“With me being a local and knowing so much about Kronk and boxing I became very close to Emanuel.

“We were very close until he passed away, I lived with the guy for about eight years.

“Emanuel was a spiritual guy. He didn’t go to church and he threw the word ‘motherfucker’ around as if it was nothing.

“But he didn’t have an evil bone in his body and he really did believe in God, he really did believe that.”

Richard found an array of jobs within the Kronk gym from matchmaking, to working the corner, to becoming the Vice President of Kronk.

In Detroit Richard took with him the teachings of Joe Frazier, but it was Steward, the ultimate teacher who taught him the business of boxing. Emanuel is highly regarded as one of, if not the finest trainer and manager the sport has been graced with.

“I believe Emanuel believed he was the best trainer ever.

“Undisputedly, I believe he was the best trainer ever.

“But as far as what made him a great trainer? The fact that he was the ultimate perfectionist. I mean everything had to be correct.

“I mean right down to the kinds of socks the fighters would wear, he would buy specific socks called Wigwam, that were a hiking sock, but they had a little bit more sponge than any other sock he found. And they wicked the sweat away.

“The white shoes he would have all his fighters wear because it drew the eye to the shoes.”

Alongside Emanuel, it was the ‘Motor City Cobra,’ who was the face of the Kronk gym. Tommy Hearns was heading for the tail end of his career when Richard got to Detroit.

“I actually did the matchmaking for Tommy’s last world title fight, which was against Nate Miller. We found Nate Miller last minute. I knew Nate Miller from Philadelphia.

“We thought that Miller and Tommy would provide a compelling bout.

“However, it wasn’t a classic but Tommy won his last title fight.”

It was Hearns who had Slone fixated to his television set during the golden era of the ‘Four Kings’.

Unbeknown to ‘The Hitman,’ he too had encountered one of Richard’s phone calls in the years past.

“Being around Tommy was amazing. We sat in a training camp in the Poconos, in Scotrun, PA.

“Tommy was training for some fight, it might have been the Uriah Grant fight which I believe he lost, his ankle went out.

“I remember speaking to him. And I said, ‘Tommy as well as we have known each other for the last ten years or whatever now, I’ve never told you this.’

“And I said, ‘When I was a kid I used to write to you.’ He once sent me a Kronk jacket that he had worn, there were business cards in the pockets and he said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me. And you never told me this?’

“I said, ‘I never told you. One night, I remember the phone ringing at one o’clock English time, and my dad getting all pissed off answering the phone.’ ‘Who the hell’s calling at this time of the night?’ And he said, ‘Well who is this?’ And the guy on the other end says, ‘Thomas Hitman Hearns.’

“So my dad got me out of bed and I had a chat with Tommy. And this is all set up by Emanuel, and I told Tommy the story and I said, ‘You’ve been an idol of mine and one of my favourite fighters.’”

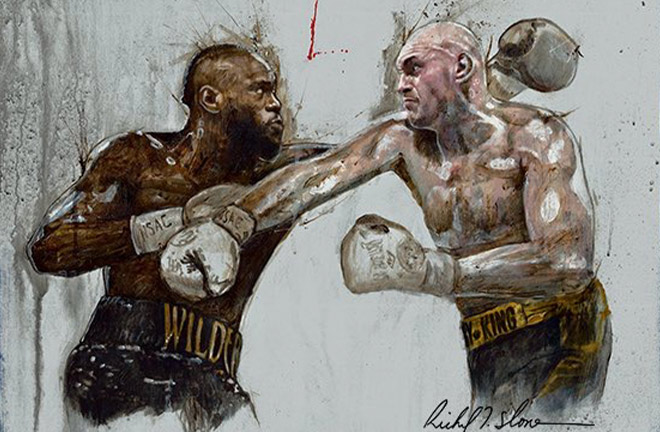

These days you will find Richard at an easel as he works on the latest front cover for fight programmes or boxing publications.

One thing is clear, boxing is still pumping throughout his veins and it always will.

Once a fighting man, always a fighting man.

“Now I’m a little bit older and now I make my money painting and I still hang around with the fight gang.

“I go down and see Tyson Fury boxing in Vegas.

“I’m always around the fight gang, I mean it’s in my blood, it has been my whole life.”