“Unbelievable! Unbelievable! With two seconds left to go Richard Steele stops the fight! Fewer than 5 seconds to go!”

As Jim Lampley screamed these immortal words over the boom of the Las Vegas crowd, the anonymity that a boxing referee normally enjoys was completely shattered for Richard Steele.

He had gone from a faceless, nameless figure in a blue shirt and a bow tie to the most controversial and fiercely debated man in boxing.

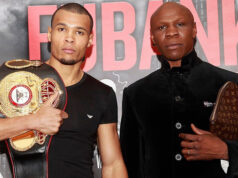

Steele had been a staple of boxing viewers’ television screens for many years, but had never yet become a figure of such negativity.

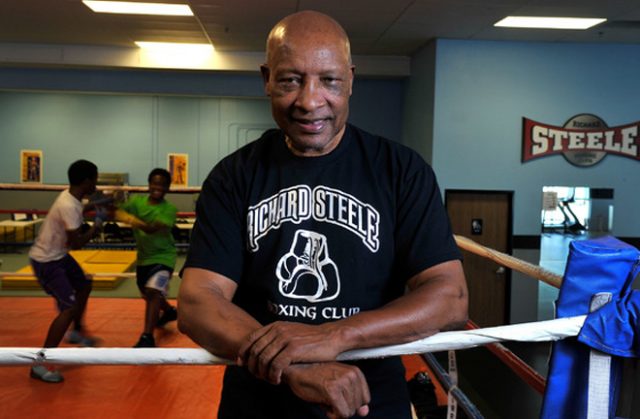

He took to boxing during his time as a United States Marine. He boxed in the same 1960’s boxing squad as Ken Norton, the man who would make his name opposite Muhammad Ali.

Steele took up refereeing when his fighting career petered out, but soon found out this was where his true talents lay.

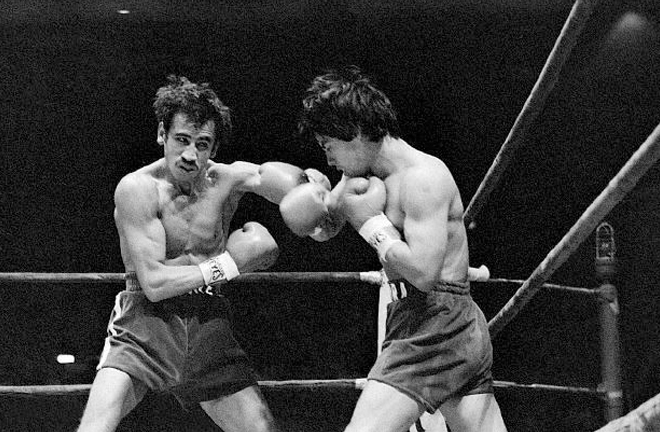

Steele’s first major fight was between Carlos Zarate and Alfonso Zamora, two undefeated Mexicans whose out of the ring rivalry would spill into the ring and cause the referee his first major issue.

During the bout a man stormed the ring in his underwear and began shouting at the fighters.

Steele reacted quickly stopping the action, pushing the boxers to separate corners and presiding as helmeted policemen dragged the intruder out of the ring.

Remaining calm and composed too when at the end of the bout the defeated Zamora’s father attacked Zarate and caused a short-lived melee in the ring.

Steele simply stood over Zamora, protecting the hurt fighter from the fracas around him.

He was praised for his ability to handle adversity and with this he began to climb the ladder of boxing refereeing.

After refereeing Aaron Pryor’s rematch with Alexis Arguello in 1983, Steele was promoted as the top referee for the Nevada State Athletic Commission (NSAC) under Mark Ratdner where he oversaw numerous World title fights.

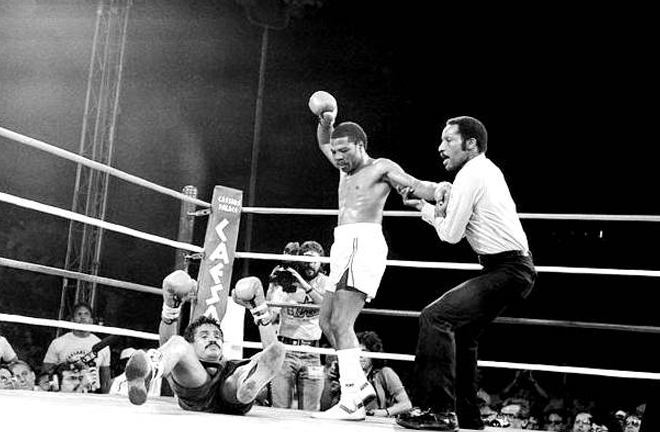

Steele was promoted at the perfect time. The deadly ‘Four Kings’ ‘Sugar’ Ray Leonard, Marvin Hagler, Thomas Hearns and Roberto Duran had begun to wreak havoc across the lower weight divisions and he found himself closer than anyone else, officiating some of those bouts.

He made his trademark by doing mostly nothing. Unlike many referees we see today, he used the art of doing nothing to his advantage.

This third man would allow the fighters to operate freely and work out of cliches and exchanges themselves and this produced some of the most dynamic contests of the 1980’s.

Hagler vs Hearns, Hagler vs Leonard, McGuigan vs Cruz and Hearns v Barkley were just a few of his most memorable fights.

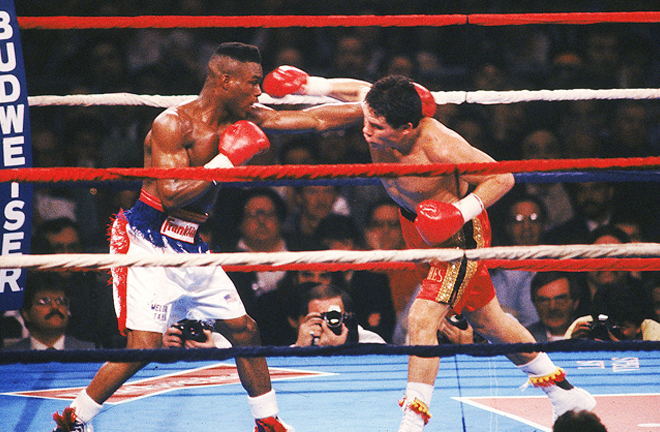

As Steele focussed his vision on the greats he was refereeing, behind him Meldrick Taylor and Julio Cesar Chavez.

Two soaring comets burning with ever more ferocity, destined to clash into one another. Little did this trifecta know that soon they would all three come to define one another.

Taylor was the 1984 Olympic gold medal winner, awarded boxer of the tournament over Pernell Whittaker and Evander Holyfield. He was a Philadelphia fighter with a flair for the dramatic.

Hand speed, footwork and classy boxing had taken him to 24-0 and an IBF world championship belt.

His antithesis was to be found in Julio Cesar Chavez.

Workmanlike, tough, rugged, the Mexican champion had embodied the virtues of his country to move to a near unprecedented 68-0.

He was also WBC champion making the clash not only a mesmerising clash of styles, but also a colossal unification bout.

“Every referee in the world, oh man, you can’t imagine how much you dream and you pray that you can get this assignment.” Steele would say of the scheduled Light-Welterweight unification bout.

On the strength of the 45 World title fights he had already refereed he was indeed given the assignment he’d wished for.

However, as there so often is in a high profile boxing event the complaints soon came flooding from the Taylor camp.

Lou Duva, Meldrick’s manager and trainer immediately objected to Steele as the referee. He would later say, “I objected to Richard Steele as the referee, not because he wasn’t competent; there was just some rumours around Las Vegas about him and Don King fighters.”

Chavez of course was promoted by King. Mark Ratner took the complaint seriously, but on a further look it was deemed baseless and the fight went ahead with Steele as the referee.

Although Duva’s complaint was probably just the usual tricks of a veteran to annoy the other side it would prove almost prophetic, and add justification to Steele’s detractors after the bout.

As the bout got underway Taylor was electric, his trademark speed made the normally speedy Chavez look cemented to the canvas.

For the first nine rounds Taylor was mercurial, flitting in and out with a grace that only a handful of great fighters ever have.

“Taylor was dominating, nobody expected that,” said Larry Merchant.

“Reminiscent of Ray Leonard at his best,” said Jim Lampley.

Even Chavez’s corner at the end of the eighth round told him he was losing badly and begged him to fight for his family.

Richard Steele however, from his unique vantage point closer even than the ringside observes, had begun to see another pattern emerge.

“I knew Meldrick Taylor was winning the fight because he was landing two to one.

“But at the same time I could see Chavez landing these hard, hard punches.

“Shots that would break bones, most of the audience couldn’t see the beating this young man was taking.”

Although Taylor was well ahead, both his eyes were badly swelled, he had paid a huge physical cost to win the rounds.

As they came out for the 12th round it became clear Chavez could smell blood.

Steele bobbed on his toes, his eyes fixed on the face of Meldrick Taylor, swollen and grotesque. Blood flowing from his nose and mouth, watching as he soaked up more of the Mexican’s blows.

Then with 25 seconds left in the fight, crack a right hand, then another, Taylor wobbles. 15 seconds, a final thudding right. Taylor crumbles. 1, 2, Steele looks down at the fallen Taylor. 3, 4, He jumps up, Steele leans right in, inches from Taylor.

The infamous question, ‘are you okay?!’

A bloodied and swollen Meldrick Taylor stared blankly into the middle distance and Steele, not noticing the red timer right behind Taylor’s head, waved his arms.

As Jim Lampley proclaimed “This is one of the strangest calls by a referee in the history of the sport.”

Richard Steele realised he had just plunged himself into one of the biggest refereeing scandals of all time.

Duva charged around the ring, boiling with anger. Chavez and King embraced, knowing they had just snatched victory from the jaws of defeat.

The first person Larry Merchant rushed too wasn’t one of the combatants, it was Richard Steele.

“I don’t care about the time, when I see a man that’s had enough, I’m stopping the fight.” Steele said when asked why it was stopped.

When that was put to Lou Duva he was predictably fiery screaming, “Bullshit! I don’t believe that at all! He was up at 6!”

The media storm was ferocious.

“He should have got the win because for 35 minutes and 58 seconds he was winning that fight.”

“Taylor fought his heart out he earned the last two seconds.”

“Richard Steele should never referee again.”

These were just some of the quotes from ringside in the immediate aftermath.

Someone once said perception is reality in boxing and this could not have been more true, as suddenly a cordial working relationship between Don King and Richard Steele had become intense friendship in the eyes of boxing.

Steele however would always deny this. “Every time that I’ve spoken to Don King it’s been in the public, in the ring.

“Don King and I have never said more than 10 words to each other at one time during the 30 years of refereeing I’ve done.”

Exacerbated by Duva’s protests, the NSAC and governing bodies all launched investigations into the fight.

The evidence that helped Steele most was medical, ringside Doctor Filp Hermansky said, “Taylor had a facial fracture, he was urinating pure blood, his face was grotesquely swollen. This was a kid who’d taken a beating to the body, head and brain.”

At the culmination of the investigations Chavez’s win stood and Steele was exonerated.

Mark Ratner said, “Richard Steele is as honest a man as I have ever dealt with.

“An upstanding individual and I believe everything he’s done in boxing he’s done for the right reasons.”

The future too would absolve Richard Steele, and ultimately prove that he may have saved Meldrick Taylor’s life.

Talyor’s speech quickly deteriorated and his decision making found him entangled in legal and financial trouble, classic signs of what we now know to be CTE, a degenerative disease caused by blows to the head.

Dr Margret Goodman, another ringside physician stated that Meldrick shows, “all the classic symptoms of someone with a chronic brain injury.”

His life after boxing has led to where Meldrick is today, arrested in 2019 for threatening someone with a firearm, ultimately a consequence of the Chavez fight.

Richard Steele, although derided for ‘robbing’ Tayor of his victory history has, to me, proved that this story ultimately is one of controversy but vindication.

Richard acted without regard for boxing, without thought to winning or losing, purses and management contracts. He acted to save a hurt young man, and in doing so, might have saved his life.

The stoppage is often debated as a topic in boxing, as well as this stoppage in particular.

However, its lesson is when analysed not quite what it appears.

Bad stoppage, early stoppage, fight until the end are all common boxing parlance, but empathetic stoppage, merciful stoppage or giving someone a chance to fight another day are not.

Although there will never be a final say, learning the lessons of history remains critical.

Written by Ewan Breeze.