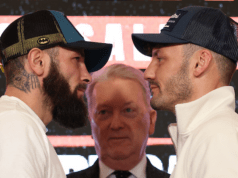

In the wake of Pacquiao-Marquez III, many have called the fight a “robbery.” The outrage at the MGM was evident, as Marquez fans slung allegations of corruption. The anger is understandable to a certain degree.

After all, Marquez has fought Pacquiao 3 times in fights with little separation between the two and has scored zero victories. You can sense the anger about the two previous fights resonating in their protest about the third fight’s result. Their belief that Marquez deserved one of those fights is within reason. Is it right for Pacquiao to just so happen to get the nod in all those close fights? Maybe not.

But let’s not get carried away.

It just sounds a little strange to hear people saying the fight is a robbery then quote their 115-113 scorecard in favor of Marquez. A refresher course in what constitutes a “robbery” might be in order Go watch Pernell Whitaker vs Julio Cesar Chavez or Lennox Lewis vs. Evander Holyfield I and you will see what a “robbery” is all about.

You can say that Marquez should have won. But a robbery? It does a disservice to those who have truly suffered robberies.

Is giving the benefit of the doubt to a mega-superstar something new? Did Marquez just stumble upon an unfortunate new phenomenon that began with the Pacquiao era? Just about every transcendent boxing star has been the beneficiary of this type of treatment. We can debate the merit of the unspoken rule in boxing which states that you must clearly beat “the man” to become “the man.” But it is a standard practice that was begun by men who are no longer with us. It’s part of the game–like it or not.

And it’s not as if the judges are even cognizant of this phenomenon. It’s subconscious to a large degree. You can’t expect boxing judges to be nonhuman and be able to look at Manny Pacquiao like he’s just some regular pug. He’s been the face of this sport for several years. That comes with a lot of spoils–one of them being that you get the benefit of the doubt from time to time.

And Marquez’ chief second Nacho Beristain should know this. Any late advice short of “put the petal to the metal” was highly inappropriate under those conditions. For the record, the only time when Marquez wasn’t losing the fight on the cards was after the 8th round, at which point the fight was a draw.

It’s also important for people to grasp the negligible difference in scorecards they like and dislike. Surely, no Marquez fan had much beef with 114-114, so how is 116-112 in favor of Pacquiao a scandalous card? That’s 2 rounds difference in a fight where many rounds were not conclusively won. It’s not 4 rounds difference–it’s 2 rounds.

Boxing doesn’t have a score on the board. Other than MMA, there is no other sport like it. If the fight doesn’t end by knockout, judges decide the outcome. There are judges in other sports, but they appraise solo performances against each other–not two people competing at the same time.

So it boils down to individual preferences. And in rounds where it is difficult to attribute clear superiority, there are a slew of factors that figure into the equation. Some of those standards might favor the bigger-name fighter, which might upset some.

But there can actually be a liability to possessing the identity of “the man” when fans judge fights. Fighters like Pacquiao are in the position they are in precisely because they are dominant fighters. Therefore, it becomes easy to allow the mind to equate a competitive fight to failure, in a sense. When you juxtapose the image of Pacquiao’s fight with Marquez with his recent run of one-sided beatdowns, the difference is vast. It could possibly make it look like Marquez was doing better than was actually the case.

And surely everyone at the fight saw the long odds against Marquez on the board. When you see a huge underdog doing much better than expected, the mind tends to go to a certain place. You see Marquez doing far better than expected, while Pacquiao is falling short of what was forecasted. That typical Pacquiao effervescence was flattened to a degree. This dynamic tends to give Marquez the vibe of a winner. That doesn’t necessarily mean he won the fight.

The pro-Marquez throng at the MGM was passionate. Galvanized by their unity and numbers, in addition to Marquez’ great showing, they were vociferous in their support of their fighter and in their protest of the decision. And Juan Manuel’s style was very conducive to eliciting the biggest response. A counterpunching marvel, Marquez was the last one to strike. He almost always landed the final punch of the exchanges, which left a more vivid image.

In a lot of those exchanges, Pacquiao would land several punches, only for Marquez to snap his head back and send his hair flying dramatically with a crisp counter. Marquez surely won his share of those exchanges. But a lot of Pacquiao’s punches were drowned out by Marquez’ more compelling and easier-to-see-and remember counter shots. If Pacquiao lands 3 so-so shots and takes a nice counter in return from Marquez, who really wins that particular exchange?

Unlike their first two meetings, Pacquiao failed to knock Marquez down. Disappointing as that might be to some, he did inflict some damage on Marquez. He lacked some of his normal flair, but he was assertive–landing jabs and punishing straight lefts. He was slightly more insistent than Marquez in certain rounds.

I can understand the angst. Marquez did about as well as he possibly could and it still wasn’t enough. When “Dinamita” asked, “What more can I do?” at the post-fight press conference, it was hard not to feel for him a little bit. Because there wasn’t much more that he could have done. That makes it almost seem like he’s in a no-win situation. As if the boxing establishment will deny a 38-year old lightweight a welterweight victory over the best fighter in the world in the face of anything less than domination. Marquez and his supporters are within their rights to loathe what seems like an un-winnable situation.

But a robbery? No. The amount of people thinking Pacquiao won makes it hard to say that. When robberies occur, you won’t be in the press room hearing a bunch of people having it a draw or a narrow win for the alleged benefactor of the alleged robbery. After Lewis-Holyfield I, there weren’t any people saying Holyfield should have won.

Not being a huge punchstat guy, I hesitate to use that as evidence. In this case, however, the fact that Pacquiao landed 38 more punches serves as another roadblock for people trying call this a robbery. As does the fact that Marquez threw only 436 punches–142 less than Pacquiao. Unless you pack big power, 36 thrown punches a round isn’t the typical workload of a “robbed” fighter.

So let’s not get carried away and try to project our opinions as universal truths. Those who feel Marquez won are more than reasonable in thinking that, but calling it a scandal is a less lucid stance than any scorecard handed in on Saturday night.