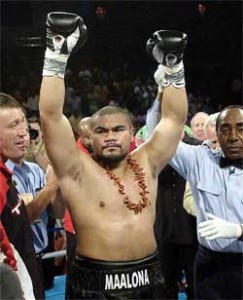

When I think of the numerous controversial fights I have seen unfold live (either in person or on television), David Tua vs. Hasim Rahman stands out, and for a number of reasons. First and foremost, it was a test of two young, up-and-coming heavyweights, and that kind of fight is always an exciting prospect. Second, the result was truly controversial and an instance where I profoundly disagree with the way the referee handled the fight. Third, it is one of those landmark bouts where I think most of the community of boxing journalists and pundits made a completely bogus analysis, allowing me to identify quite a few people who sank deep into their armchairs, never to arise. Like Trinidad vs. de la Hoya, this was a fight that I saw live, a fight that ended in polarizing fashion and a fight that made me a strident partisan about the results.

Rewind back to December 1998. David Tua was a 32-1 slugger with a frighteningly high knockout percentage, rebounding from a closely-fought, barnburner of a loss with the enigma, Ike Ibeabuchi. “The President” vs. “The Tuaman” still stands as the record-holder for most punches thrown in a heavyweight bout. Tua had quick hands, enormous stamina and thunderous power, but he was prone to losing his focus when stymied by a taller guy with reach who choose to stick and move on him, as the Maskaev fight in 1997 had shown. Hasim Rahman, whom I’ve met on several occasions and often refer to as “The Baltimore Knucklehead,” was a strong, hard-hitting fighter with freakishly long arms and some talent. However, Rahman had come to boxing late and had not progressed far beyond the “1-2-clinch” school of heavyweight fighting. “The Rock” also had a tendency to fade badly in the late rounds.

Rahman came out with a good game plan that night in Miami. Rather than punching and holding, which was his strong suit heretofore, he stuck and moved. He threw a lot more punches in the process, but noticeably fewer rights. Rahman and his corner recognized that clinching with Tua was a losing proposition, and the more Rahman threw his right the more it opened him to a left hook over the top. Rahman essentially tried to repeat what Oleg Maskaev had done more than a year before, but the difference was that Rahman has stamina issues and wasn’t used to throwing and moving all night. One of the things the so-called experts miss in watching that fight is that Rahman was tiring and noticeably slowing in the late rounds.

Enter Round 9. The bell rang and Tua instantly fired two hard left hooks over the top. Rahman was utterly crushed and collapsed like a marionette with its strings cut. This is also where many pundits go wrong. While undeniably a foul, a lot of people who plainly didn’t watch the fight or have an agenda, describe this incident as if after the bell Rahman dropped his hands and was turning to go back to his corner when Tua attacked, portraying it as a stab in the back. The reality is that in the instant after the bell rang, a frustrated Tua saw his opening and fired. He shouldn’t have, and referee Telis Assimenios handled it badly. Intercepted by Lou Duva in the middle of the ring, Assimenios did nothing. Many armchair boxers, who have never fought (let alone judged or refereed) a fight, complained a disqualification was justified, and in so doing merely revealed how little they know about the rules of the sport and its practicalities. The appropriate response would have been to give Rahman five minutes or more to recuperate, since the foul wasn’t flagrantly intentional and Rahman could continue.

In the 10th, Tua pounced on a still wobbling Rahman, driving him onto the ropes and producing a TKO. Once again, the so-called experts often get this one wrong, Many thought Rahman was still fighting, because he was supposedly moving his head and had his guard up. The assertion is ridiculous. Rahman was covered up, didn’t throw a single punch and was virtually sitting on the ropes throughout the furious attack by Tua. The stoppage was completely justified.

In my opinion, if Rahman had gotten his five minute recuperative break, the result would have been merely postponed into the 11th or 12th Round. As I wrote before, Rahman was fast running out of gas. He got nailed by Tua at the end of Round 9 not because the bell rang, but because his feet were giving out and his hands coming down. The Baltimore Knucklehead was not a man who ever displayed miraculous recuperative powers. If Rahman had received a five minute break or had never been fouled, odds are he would have had the starch knocked out of him anyway. Aware of the fact that he was far behind on the scorecards, Tua would have launched the same kind of assault that flattened Oleg Maskaev and kayoed him, as Rahman was neither as slick as Chris Byrd or as physically imposing as Lennox Lewis.

The two fought an inconclusive rematch in 2003. By then, David Tua was embroiled in management disputes that would lead to a two-year hiatus immediately afterwards, and would continue to bedevil Tua’s boxing career until relatively recently. Rahman went on to be knocked out by Oleg Maskaev twice, win and lose the heavyweight championship to Lennox Lewis, see Evander Holyfield give him the world’s biggest bump on the noggin, and get whipped by Wladimir Klitschko.