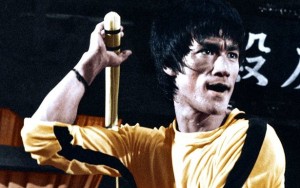

Even as it nears four decades since the tragic, untimely death of Bruce Lee, questions still linger about his connection to the continually evolving realm of mixed martial arts. Given the variety of techniques Lee incorporated into his own martial arts, was he the first mixed martial artist? If he was, what led him down that path? Surprisingly to some, if you study Lee’s techniques and philosophical beliefs on training, combat, lifestyle, and more, the most obvious connection is actually between Lee and the sport of boxing.

In a recent interview, Shannon Lee, Bruce’s daughter who runs Bruce Lee Enterprises and the Bruce Lee Foundation, provided great insight on these subjects.

Bruce Lee’s Connection to Boxing

At a recent press conference, Manny Pacquiao said that “Bruce Lee is my idol,” and he’s not the only person in the world to share the sentiment. Lee has legions of fans spread across the globe, and as the years pass, the collection only grows.

Pacquiao’s abilities and accomplishments would have made his idol quite proud, and he may just be Lee’s closest heir in the combined worlds of combat, martial arts, social action and entertainment. That Pacquiao looks the part, with his new haircut and chiseled physique, acts the part, with his deflecting, charming personality, and has the potential to explode violently with an unparalleled combination of speed and power, makes the comparison that much juicier.

Even as Pacquiao borrows from Lee, Lee borrowed heavily from the world of boxing. Many people, even Lee’s fans, do not realize how large a role boxing had in developing Lee’s unique style, as well as his beliefs about the best approaches to combat. Shannon Lee says that her father “was a huge fan of the sport, he studied the sport, he took a lot from it when it came to his own style of fighting.”

That style, Jeet Kune Do, “the way of the intercepting fist,” was laid out in a popular text called The Tao of Jeet Kune Do, posthumously published in 1975, two years after Lee’s death. It was compiled from years’ worth of notes, illustrations, principles and writings.

Before Jeet Kune Do got its official start in 1967, Lee first developed a style of martial arts he called Jun Fan Gung Fu, or Bruce Lee Kung Fu, which was taught in several studios he opened in the mid-1960s. Jun Fan Gung Fu was Lee’s approach to the Chinese martial art Wing Chun, and he eventually found that even his own spin on this style was too restrictive. He realized the need for continued evolution and the incorporation of fresh ideas.

The Influence of Boxing on Jeet Kune Do

Contrary to some of the myths circulating on the Internet, Lee never fought professionally as a boxer and his amateur boxing experience amounted to only one competition, in 1958, while a teenager in high school in Hong Kong. According to Shannon, Lee won the bout without having had any boxing training, relying only on Wing Chun. However, the long-term influence of boxing on Lee’s technique and style would be far reaching, particularly as he moved away from the classical martial arts and began developing his own philosophy of fighting.

Lee’s love of boxing led him to develop a vast collection of books, films and tapes, so that he could learn from those that did it best. For example, Lee aimed to mimic the body mechanics and power generation that helped Jack Dempsey level his opposition and made him one of the most fearsome heavyweight champions of all-time. According to Shannon, Lee went so far as to exchange letters with Dempsey, hoping to pick his brain, “about Chinese martial arts and the art of Chinese boxing compared to western boxing.”

Lee drew directly from what he saw Dempsey, Muhammad Ali and other great fighters do in the squared circle. He also worked out with professional boxers, and Shannon noted that he would stand in front of a mirror as he watched boxing films and “mimic some of the moves and follow along.”

More specifically, the Bruce Lee Foundation website maintains that within Jeet Kune Do, the “vertical-fist jab, proper alignment, striking surface, hip rotation, and kinetic chain sequence all come from boxing.”

There are entire sections within The Tao of Jeet Kune Do filled with descriptions, illustrations and notations devoted to boxing techniques, such as the principles behind all of the punches used and the types of defensive tactics deployed. While carefully composed, it’s a near stream of consciousness as Lee pores over the minutiae of punching, counterpunching, evading, footwork, mobility, slipping an opponent’s attacks, fighting while moving backwards and more. For example, his analysis of the jab offers that:

“The lead jab is a ‘feeler’. It is the basis of all other blows, a loose, easy stinger. It was a whip rather than a club. Ali’s theory is to picture hitting a fly with a swatter… Used correctly, it is the sign of the scientific fighter, who uses strategy rather than force. It requires skill and finesse as well as speed and deception (broken rhythm). Keep in mind that there is nothing worse than a slow jab, except one which is telegraphed.”

This type of analysis shows Shannon how “scientific” her father was about his martial arts training and beliefs. Nothing Lee did was by chance, or was without reason, and everything was studied down to its finest points. When all was said and done, boxing was one of the key areas of source material and inspiration for what would become Jeet Kune Do.

The Evolution of Mixed Martial Arts

By evaluating techniques and principles from multiple disciplines in order to establish his own philosophically based approach, and in taking that approach and competing against practitioners of other styles, Lee was well ahead of his time. In the History Channel special How Bruce Lee Changed the World, UFC president Dana White goes as far as to say that Bruce Lee “is the father of mixed martial arts.” It’s not much of a stretch to agree.

Shannon describes her father’s approach to martial arts and the teachings of Jeet Kune Do in this way:

“In order to be the best fighter, you have to be able handle any situation in which you can find yourself. So if you find yourself on the ground, you have to know what to do there. But at the same time he didn’t just go out there and learn 7, 8 different arts and just say ‘oh what should I do here now? I should do this.’ It was much more fluid, it was actually a way of like, let’s not name any of it, I’ve got two arms and two legs and a person in front of me. What do I need to do and how do I need to flow in order to chop down their defenses and be victorious?”

The practice of martial arts, up to that point in time, was largely bound within the confines of only one system or style. This limited one’s options and led to each style having its own explicit drawbacks. Lee’s Jeet Kune Do was different though; it was a “style without a style”… a style which thrived by “using no way as way”… and “having no limitation as limitation.”

However, Lee didn’t just randomly compile a hodgepodge collection of techniques and call it a new martial arts style. In the words of the Bruce Lee Foundation website, “(e)ach weapon was subject to scientific analysis, modified, and tested in fighting situations.”

In this way, Jeet Kune Do was developed and refined based on principles such as efficiency of motion, quick-striking, adaptability and, according to the Bruce Lee Foundation, “the idea that you can set up your opponent so that you will be able to intercept him in his most vulnerable state”.

Lee repeatedly stressed that, “I have not invented a new style, composite, modified or otherwise, that is set within distinct form as apart from this method or that method.” For Lee, Jeet Kune Do was as much a philosophy and mindset, as opposed to a strict definition of technique and rigid actions. He said, “let me remind you Jeet Kune Do is just a name used, a boat to get one across, and once across it is to be discarded and not to be carried on one’s back.”

Shannon says that she doesn’t, “look at what my father did as necessarily being MMA,” but that she does “look at it like the beginning of [mixed martial arts].”

Physical and Mental Dedication

Bruce Lee was also ahead of his time with his approaches to training and nutrition, along with the complete commitment and dedication that he had for his craft. Lee said that, “training is one of the most neglected phases of athletics. Too much time is given to the development of skill, and too little to the development of the individual for participation.”

He realized this for himself after a 1964 challenge match against Chinese martial artist Wong Jack Man. Although Lee won this fight, he wasn’t able to physically accomplish what he wanted, and what he believed his techniques made him capable of doing.

His own body was holding him back, and according to Shannon, this incident, “was really the beginning for him of breaking away from the more narrow, traditional martial arts training to opening himself up to different possibilities, and also, to physical conditioning, because he realized he needed to be in great physical shape in order to be able to execute his technique.”

Bruce Lee’s training was notoriously rigorous, honed with his typical scientific, refining approach. Even more famous than his training though, are his feats of strength, both the ones bound in fact and the ones which have been embellished or fabricated entirely, passed down like mythical lore over the decades.

Many of these come from collections of interviews and stories on Lee put together and edited by John Little. For example, in one story, penned by Don Duncan and found in the compilation Words of the Dragon: Interviews 1958-1973, Duncan describes Lee as performing “stunts”, such as, “[h]aving a man from the crowd, proud of his reflexes, hold a dime in the palm of his outstretched hand. Lee, his hand hovering a foot above the outstretched hand, proceeds to remove the dime and leave a penny-before the other can clench his fist.”

In an interview with BlackBelt Magazine, a man named Ed Hart offered a description of a full contact match that Lee had in 1962 against a Japanese black belt karate practitioner. He says that, “the fight lasted exactly 11 seconds – I know because I was the time keeper – and Bruce had hit the guy something like 15 times and kicked him once. I thought he’d killed him.”

In The Dragon and the Tiger: The Birth of Bruce Lee’s Jeet Kune Do, written by Sid Campbell and Greglon Yimm Lee, a story is told about Lee training by “stabbing and slicing his hands” into buckets of gravel. The method was taught to Lee by a martial arts instructor known as Gin Foon Mark, referred to in the text as Sifu Mark, sifu being the Chinese word for teacher or tutor. Sifu Mark suggested building up the training “until he could do 500 repetitions a day” starting “with small-grained textures” and progressing towards “coarse rocks”.

So legendary is Lee, that the culture of mythology and lore around his feats has passed down to his pupils. Perhaps his most notable student, Chuck Norris, has been the center of a tongue-in-cheek homage to his physical abilities and persona which has become an Internet phenomenon. Known as Chuck Norris Facts, a quick glance at the website offers such gems as “Chuck Norris can cut through a hot knife with butter” and “death once had a near-Chuck Norris experience”, amongst thousands of other one-liners.

For Shannon, it’s impossible to keep track of the hype surrounding her father, and she laughingly admits that “he couldn’t leap tall buildings in a single bound.” Nevertheless, Lee’s training and physical capabilities were extraordinary, and many of these “physical feats” and other claims are taken from firsthand sources.

Lee’s intense training though eventually led to injury. He severely injured his fourth sacral nerve while weightlifting without warming up in 1970. Afterwards, he was basically bedridden for six months.

While he was told he would never practice martial arts again, the Bruce Lee Foundation biography states that he, “instituted his own recovery program… gradually built up his strength… [and] as can be seen by his later films, he did recover full use of his body.”

During this time, much of Lee’s thoughts on Jeet Kune Do, which would later from the basis of The Tao of Jeet Kune Do, were hashed out and written down.

This ability to make the most of any situation, even “an extremely frustrating, depressing and painful time,” was one of Lee’s strengths. When forced to try to explain the one factor that made her father so unique and special, Shannon says that her father would, “not only just push through adversity, but when challenged with adversity, would see if there’s maybe a different approach instead of just banging your head against the wall.”

She continues, “he had the drive… coupled with the ability to learn from his own mistakes,” and the belief that, “I don’t just keep on one path regardless of it is working or not. If this path is leading me in the wrong direction, I find another path.” Bruce Lee had the desire to be the best, the mental strength to forge ahead even at the worst of times, and unending physical commitment.

Bruce Lee, Boxing and Pacquiao

Dan Inosanto, one of Bruce Lee’s foremost students who also helped to put together The Tao of Jeet Kune Do, has long been one of the main voices on Bruce Lee’s life and martial arts. He once said that, “(t)here’s no doubt in my mind that if Bruce Lee had gone into pro boxing, he could easily have ranked in the top three in the lightweight division or junior-welterweight division.”

Inosanto may be selling his mentor a little bit short there, although he was likely referring to near-immediate results as opposed to what could have been accomplished after a life of training. Nevertheless, Inosanto is a Filipino-American, and as such, may have an affinity for a certain boxer-congressman with grand plans and unmatched fistic capabilities… and that brings us back to where we started.

“I think Manny Pacquiao is amazing,” Shannon says, and she sees the similarities in the two men. Still, she’s reminded of her father, and what he represented, not only by Pacquiao, but by anyone who carries on the philosophy that, “it’s not just about winning but living a certain lifestyle and really honing one’s craft to the best of their ability. Anytime you see that happening, that’s the mark of a warrior, and that’s the mark of what my father was.”

The closing line in the biography provided by the Bruce Lee Foundation website reads: “The world lost a brilliant star and an evolved human being that day. His spirit remains an inspiration to untold numbers of people around the world.”

Shannon believes that inspiration is her father’s biggest legacy, and clearly Lee has inspired Pacquiao, the world’s best boxer, and a humble hero if there ever was one.

Still, if Lee were alive today, it would be easy to envision him sending Pacquiao letters, hoping to gain some insight into how he attacks his opponents, hoping to find a way to improve his own fighting skills. Somewhere, imagining that connection, there’s a coy smile on Bruce Lee’s face.